Introduction

Over the past decade, international terrorism and the migration crisis in the Mediterranean have drawn international attention to the security situation in North Africa and the surrounding Trans-Sahara region. High-profile incidents like the wave of popular unrest known as the Arab Spring and subsequent Libyan civil war captured headlines and compelled Western military inventions. Yet in the shadows another threat has grown and now poses an increasingly thorny challenge to regional security: transnational organized crime. This post will examine the history and present context of trade and smuggling activity across the Trans-Sahara and illustrate the connections that bind this pivotal region to the rest of the world.[1]

Regional overview and context

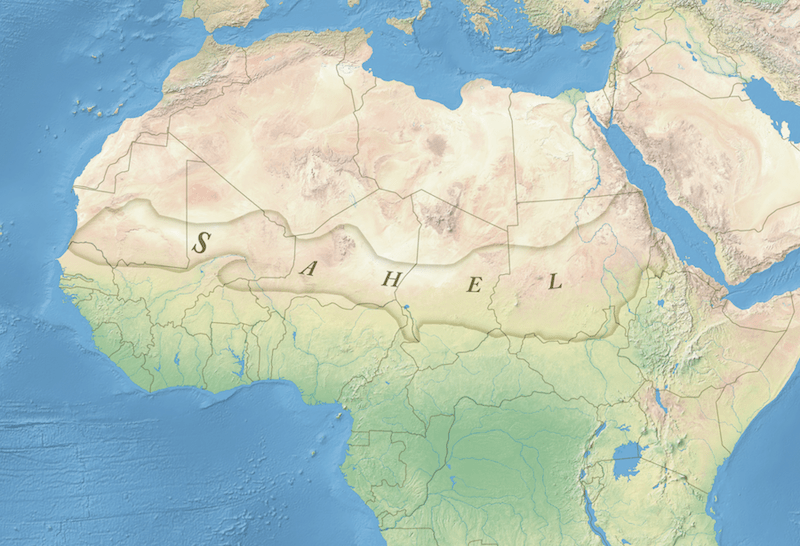

The Sahara occupies a strategically significant transition zone between Europe, the Levant, and the wealth of sub-Saharan Africa. For thousands of years the desert has served as a thoroughfare for a dizzying array of goods both legal and illicit, from salt, oil, and narcotics to AK-47s, stolen Peugeots, and counterfeit Viagra. An increasing amount of people travel north both freely and against their will, seeking their fortunes or smuggled into a life of slavery abroad. These informal economies blur national borders and form an important part of the local economy and culture. In Morocco, for example, the black market in cannabis production is estimated to account for one tenth of national gross domestic product (GDP).[2]

The region’s central location spurred the creation of commercial crossroads connected to neighboring worlds. In northern Africa, the Maghreb states- Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Libya- neighbor Europe and its wealth and serve as the terminus for human and commercial traffic from and to the Sahel transition zone in the desert, where Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan interface with East and West Africa and the Americas and Asia beyond. Their black markets are inextricably intertwined. The spread of organized crime reflects the general tolerance or even encouragement and cooption of these groups by regional governments.[3]

In some cases, repressive regimes have worked with criminal groups to pacify restive borderlands. Libya offers the starkest example. Prior to the 2011 revolution, the Qaddafi regime provided sanction to pro-government tribes and criminal groups to continue smuggling operations in exchange for kickbacks and loyalty. This often translated into these actors serving as proxy forces for the Libyan security services against political dissenters, terrorism, and rebel groups.[4]

Tacit government support for traffickers in Chad stems from a belief that this traditional trade is a stabilizing presence along the border and will prevent tribes from joining the Islamic insurgency. In one particularly notorious case, the N’Djamena government even appointed Chidi Kallemay, a widely known drug trafficker, as a chef de canton (a de facto mayoral role) in the borderlands in 2014.[5]

Arms trafficking and terrorism

As popular unrest toppled governments across the trans-Sahara in 2011, organized crime networks took advantage of the disorder and in many places consolidated their control over outlying areas. However, the plunder of Qadaffi’s arsenals during and after the Libyan revolution flooded the region with weapons and created chaos that has disrupted historical trade routes. Widespread lawlessness in the border regions of Libya, Mali, Niger, and Chad, fueled by the proliferation of Libyan military weapons and materiel, added to the increasing governance challenges.[6]

Mokhtar Belmokhtar, an al-Qaeda in the Islamist Maghreb (AQIM) leader, told the Mauritian news agency ANI in late 2011 that “we have been one of the main beneficiaries of the revolutions in the Arab world”. The 2012 attack in Benghazi against United States government facilities that led to the death of Ambassador Christopher Stevens brought Libya and its looming crisis to the forefront of global security concerns. With a multitude of factions carving out fiefdoms across the country as central authority crumbled, fears of regional arms proliferation metastasized alongside the civil war. The Daily Mail quoted Western intelligence officials claiming that Libya had become “the Tesco [supermarket] of the world’s illegal arms trade”.[7] Despite the initial concern, international authorities have not detected any evidence of significant arms flows from Libya beyond its immediate neighbors as well as Gaza, Syria, and Mali. Proliferation is believed to have been less dramatic than expected due to the coordinated international response to prevent Libyan arms trafficking and increased violence within the country, which led to higher demand domestically. Large weapons stocks have also been imported to Libya by security partners seeking to bolster its faltering security forces. United Nations member states reported bringing 65,000 assault rifles, 15,000 submachine guns, 60,000 handguns, and 60 million rounds of ammunition into Libyan territory prior to 2014.

The impact of Qaddafi’s looted arms depots has been acute in the frontier zone of southern Libya, which has become synonymous with anarchy. Fragmented, autonomous, and cross-border ethnic militias, like the Tubu, broker deals with regional governments based on political expediency. Chad and the Libyan transitional government focus on cultivating these groups, while Sudan deploys its notoriously brutal Rapid Support Forces- themselves often accused of complicity in trafficking and other criminal activity- along its border to both intercept Darfur rebels in the ongoing conflict there as well as hunt the hundreds of fighters fleeing the Islamic State’s collapsing Sirte redoubt. The presence of American special forces advisors on the ground and coalition air assets in support has reinforced local militaries, although the threat from Islamic insurgents remains credible, as the deadly ambush in southwestern Niger in October 2017 illustrates.[8]

Libyan arms also fuel the ongoing insurgency in Mali, where Tuareg and Islamist rebels seized nearly half of the country in 2012. After a French-led military intervention re-established government control over the restive northern regions, emphasis transitioned to counterinsurgency via Operation Barkhane. Named after a crescent-shaped dune in the Sahara, Operation Barkhane highlights the continuing neocolonial concerns of France and other Western powers. Then-defense minister Jean-Yves Le Drian stated that the objective of Operation Barkhane was to “prevent… the highway of all forms of traffics to become a place of safe passage, where jihadist groups between Libya and the Atlantic Ocean can rebuild themselves”, noting the serious consequences for international security if the region were allowed to return to anarchy.[9]

The presence of the Islamic State, and its uneasy partnership with Boko Haram (now sometimes known as Islamic State West African Province, or ISWAP), demonstrates that those consequences could be far-reaching if left unchecked- particularly as violent extremist organizations (VEO) compete and engage with criminal syndicates in regional black markets.[10] Although estimating the composition and strength of terror cells notoriously difficult, data suggests that approximately 500 Islamic State fighters remain in Libya, with 425 more pledging allegiance to a separate Islamic State in Greater Sahara branch as of summer 2018.[11] The group remains motivated and dangerous, and derives much of its funding for African operations through criminal activities like kidnapping, extortion, and smuggling. Terrorism and transnational crime have become increasingly enmeshed.[12]

Drug trafficking

One of the most lucrative activities of trans-Saharan criminal organization is drug trafficking. Historically contraband cigarettes and the ubiquitous Moroccan marijuana and hashish formed the bulk of African narcotics, although more valuable substances like cocaine and heroin began to make an appearance in 1970s West Africa as South American cartels sought staging areas for European markets. Cocaine harvested in the Andes poured into ports and airfields in Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and Ghana. By 2005, it became clear that shipments worth billions of dollars were moving through one of the least stable parts of the planet. So much cocaine was arriving in West Africa that if it had made it to Europe, the street value would have exceeded the GDP of many of the nations they transited through, indicating that the smuggling networks had at least as many resources at their disposal as the impacted states.

A lack of equally lucrative commercial opportunity increased potential for other forms of economic activity, and corruption risks threated good governance and stability. After a coup in Guinea toppled president Lansana Conté in 2008, evidence came to light that revealed widespread government collusion and support for cocaine trafficking. Mauritania, The Gambia, and Sierra Leone experienced other high-profile corruption cases.[13]

Historically delivered via boat from Brazil, Uruguay, and Peru, cocaine now typically flies to Africa on private aircraft, mostly through flights originating in Venezuela, as maritime interdiction heightened. Fortunately, the discoveries of sizeable shipments in the early 2000s sparked awareness and alarm, and subsequently increased law enforcement helped push much of the South American cocaine to other routes. A new understanding of drug trafficking specifically and transnational crime syndicates generally as an international security threat drove Western attention and resources to combat the issue, although efforts remain indecisive and ongoing.[14] Outside intervention and more policing resulted in a significant drop from a peak of 47 tons trafficked in 2007 to 18 tons in 2013. That haul would have netted $1.25b in the European wholesale market, or roughly the GDP of Guinea-Bissau.[15]

As cocaine routes from South America became increasingly policed, large-scale local drug manufacturing began to emerge. Previously, traffickers based primarily in Nigeria had shuttled heroin and cocaine from diaspora communities near production areas like Sao Paulo, Brazil, Bangkok, Thailand, and Karachi, Pakistan to other diaspora communities in consumer countries in the global north. Today methamphetamine, which has many advantages over plant-based narcotics like heroin and cocaine from a production standpoint, is the drug of choice. Low start-up costs, readily available ingredients (including common decongestants available over the counter in local bazaars), and the ability to cook virtually anywhere have led to an explosion in West African synthetic drug production. Guinea, Niger, Togo, and Liberia are believed to harbor many rural production sites, although Nigeria continues to be the center of Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) narcotics trafficking.

The availability of other precursor chemicals, like ephedrine, in commercial quantities poses the biggest issue for would-be drug kingpins. However, the lightly regulated West African pharmaceutical industry, coupled with pervasive corruption, provides a semi-regular pipeline of psychotropic substances. Ephedrine illustrates the globally interconnected nature of this drug trade, which involves commercial air couriers bringing in the raw materials from East and South Asia, local production, and then export through land, sea, and air routes to international buyers. While Europe consumes most of the cocaine and heroin coming through West Africa, couriers bearing methamphetamine target the high-value meth markets in South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand.[16]

Human trafficking

Since 2014, thousands of Africans have fled poverty, conflict, or other difficult conditions at home in search of European asylum. Thousands more have been trafficked against their will. In Libya in particular the demarcation lines between migrants and victims of trafficking have become blurred due to the reliance on smugglers as the primary transportation conduit. The journey from sub-Saharan Africa includes caravans through the desert to Mediterranean ports and finally the often-deadly sea passage to Europe. More than 12,000 Africans have died seeking asylum in Italy alone. Over 600,000 have arrived in the past 4 years.[17]

The regional refugee crisis has become one of the signature issues heightened and fueled

by human trafficking networks. A recent International Organization for Migration study found that 76% of African migrants in Italy had experienced at least one indicator of human trafficking and other exploitative practices during their voyage.[18] An estimated half a million migrants have attempted the dangerous Mediterranean sea crossing since 2014, and despite massive immigration enforcement and border patrol efforts by the European Union and its member states the rate of departures has remained largely stable. The geographic scope of migrants has increased as more people seek asylum, and the proportion of fatalities along the way has subsequently risen as well.[19]

A central and seemingly intractable factor in the migrant crisis remains the chaotic nature of post-revolution Libya. The failure to establish a stable transition government, competing militias that govern growing fiefdoms across the country and effectively hold Libya hostage, widespread corruption and criminality, and the overall degradation of the economic and security environment have led to a “free-for-all”. The breakdown of the rule of law empowers smugglers, who have always played a role in the Libyan economy, to move oil, arms, narcotics, and people with complete impunity.[20]

Potential solutions

Given the multi-faceted and historical nature of trans-Saharan criminal networks, effectively confronting this threat will require close and thoughtful international coordination. North Africa has historically served as a thoroughfare for international trade, and black markets always grow in the shadows of licit ones. Without meaningful reform and investment in the security infrastructure and border capacity of Maghreb states this trade will only continue to grow.

Western governments have consistently underestimated, if not completely ignored, the destabilizing effects of organized crime in the region. As outlined earlier, the Islamic State and other terror groups can also be considered criminal networks given their reliance on illegal activities for funding. Sahel governments have often been tempted to use organized crime as a political resource by allowing their associates to benefit from criminal activities. This has clear implications for any policy approach to the challenge of transnational crime in the region, as concentrating on legal and security capacity building makes sense only if governments are aligned with efforts to combat criminality and corruption.[21]

Through their migration policies, European countries have increasingly sought to block migrants in transit countries, well before they reach Europe—be it through deals with relevant governments, or through arrangements with local forces on the migration corridors. However, Europe’s dream of a “Saharan wall” remains riddled with ratlines and smuggling routes.[22]

Accelerating the acceptance and adoption of technology to combat transnational crime and human trafficking offers one potential solution. Tech Against Trafficking, a coalition of technology companies dedicated to this issue, is working to identify and build a suite of tools for governments and non-governmental organizations to deploy in the field. Thorn, an app that combats human trafficking and child sexual abuse in the United States, presents a case study in effective use of innovative technology and partnerships. Working with big technology companies like Facebook and Salesforce, and providing its data to law enforcement and governmental partners, Thorn has enabled thousands of children to be identified, tracked, and rescued from nightmarish scenarios. Similar tools might be developed for use in the trans-Sahara human trafficking trade, although more austere conditions and less technologically-savvy local partners make this a challenge.[23]

Coordinated international action may be the most effective weapon against transnational crime. The G5 Sahel Alliance, a French-led coordination effort to bring together the governments of Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, and Niger, presents one example of this. The initiative seeks to increase development activities and directly respond to the needs of local populations, especially in the borderlands, to increase legal economic opportunities and security. By addressing common challenges and promoting regional development, the G5 Sahel Alliance could build governance capacity and deny transnational crime and terror groups safe haven in uncontrolled zones.[24] In the rugged trans-Sahara, this will be easier said than done.

-FWS

[1] https://atlantic-community.org/transnational-crime-in-north-africa/

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-08-01/moroccos-marijuana-farms-may-become-legal

[3] https://atlantic-community.org/transnational-crime-in-north-africa/

[4]https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/ia/INTA93_4_08_Husken.pdf

[5] http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/U-Reports/SAS-SANA-Report-Lost-in-Trans-nation.pdf

[6] https://cco.ndu.edu/News/Article/1171858/brothers-came-back-with-weapons-the-effects-of-arms-proliferation-from-libya/

[7] Ian Drury, “Don’t Turn Syria into a ‘Tesco for Terrorists’ like Libya, Generals tell Cameron,” Daily Mail, June 17, 2013.

[8] http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/U-Reports/SAS-SANA-Report-Lost-in-Trans-nation.pdf

[9] https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/france-launches-new-sahel-counter-terrorism-operation-barkhane-1456646

[10] https://softlinkx.com/firewatchold/uncategorized/islamic-state-in-the-greater-sahara/

[11] https://ctc.usma.edu/islamic-state-africa-estimating-fighter-numbers-cells-across-continent/

[12] https://www.cfr.org/blog/islamic-state-presence-sahel-more-complicated-affiliates-suggest

[13]https://www.unodc.org/documents/toc/Reports/TOCTAWestAfrica/West_Africa_TOC_COCAINE.pdf

[14] Ibid

[15] https://www.unodc.org/documents/toc/Reports/TOCTAWestAfrica

[16]Ibid

[17] https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Reitano-McCormack-Trafficking-Smuggling-Nexus-in-Libya-July-2018.pdf

[18] https://www.iom.int/news/ mediterranean-human-trafficking-and-exploitation-prevalence-survey-iom

[19] http://globalinitiative.net/human-trafficking-smuggling-nexus-in-libya/

[20] http://www.regionalmms.org/images/DiscussionPapers/Beyond_Definitions. pdf

[21] https://carnegieendowment.org/2012/09/13/organized-crime-and-conflict-in-sahel-sahara-region-pub-49360

[22] http://globalinitiative.net/accelerating-the-use-of-tech-to-combat-human-trafficking/

[23] https://www.thorn.org

[24] https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/defence-security/crisis-and-conflicts/g5-sahel-joint-force-and-the-sahel-alliance/